To define a brand’s personality or character is often perceived as advertising hocus-pocus. One of the reasons is of course that we who work with brand development fail to convey the value of a well-defined brand personality. Another is that the result often seems vague and difficult to apply in practice. But the fact is that a strong brand personality can often be the crucial distinguishing factor that creates preference for your brand and long-term, profitable customer relationships.

What and why

Brand Personality, or brand character, is about the characteristics that your target group associates with your brand. It’s about conveying the emotional associations – not the rational. The whole point of Brand Personality is to add a (differentiating) dimension to a brand that the product alone cannot convey. The idea behind this thinking is that this particular dimension will contribute to strengthening the customer’s emotional relationship with the brand, which in turn strengthens preference and loyalty.

To identify and formulate a company’s (or product’s) Brand Personality often requires association- and word-choice exercises. The result tends to be a number of adjectives – preferably three if the consultant is to decide – that are expected to summarize and describe the very complex relationships that constitute a company or product’s personality traits. But what does it actually mean for the seller in Portugal that your company is a dolphin? Or that it is associated with BMW, rather than Skoda, and that the brand will be perceived as ‘Knowledgeable, Flexible and Dedicated’? And do these associations and adjectives communicate the same personality traits for employees and customers in Helsinki, New York and Beijing?

Usefulness

The concept of Brand Personality was originally conceived by the advertising agency Young & Rubicam (and is basically the same as “Brand Character”, which is a registered trademark owned by Gray Advertising). If they are the font of the association games and word-choice exercises I have no idea. But I firmly believe that the phenomena, with very few exceptions, are a waste of time and money. Perhaps they mean something very specific and precise for the agency and marketing manager who did the job but, for the rest of the organization, they are perceived, in my experience, as so much corporate BS. And, if you change agency or marketing manager, the company’s Brand Personality will probably be one of the first things that appear on the “we gotta do something about this” list.

Do not misunderstand me: Brand Personality is important. Very important. A strong brand personality can often be the crucial, distinguishing factor for your brand. The reason is logical: emotional relationships are stronger than rational, because the emotional relationships can create loyalty beyond rational argument. They make competitors’ rational arguments less important, your customers become more lenient towards your mistakes or substandard product performance, and you get recommended more enthusiastically and more often.

A better way

Fortunately, there is a more efficient way to identify and define a brand’s personality (which is also significantly better scientifically informed). Let’s call it “Brand Archetyping”, because the starting point is the archetypes that we all carry within us.

If you study religions, myths and legends from different cultures and times you will discover that they contain roughly the same cast of characters. Compare, for example the gods of Hinduism and the Asa faith with the gods in Greek mythology. There are distinctive creators, rulers, heroes, virgins, explorers, lovers and at least one that portrays the common man.

It is these characters, or ur-types, which are called archetypes. According to Christopher Vogler, screenwriter for Disney (The Lion King, Aladdin, Hercules, etc.), they are used consciously and diligently by the film industry, because they facilitate storytelling:

” … As soon as you enter their world, you will be aware of recurring personality traits and relationships.”

The modern archetype theory was launched by Carl Jung. He analyzed and sorted archetypes, and claimed that they possess cross-cultural communication skills because, he said, they reflect our collective subconscious. In the archetypes we recognize our own impulses, needs, fears and desires. Archetypes, according to Jung, are hardwired in us all.

Each archetype is represented thus by a history and a pattern of behavior that we can relate to. These personality patterns, as we learn in early childhood and then pass on to the next generation, are processed very quickly in our brains. We uncritically accept the characteristics, because they reflect our world.

And so it is these immediate connections that you can use to give your brand an unassailably clear personality – a personality that conveys the same story for a salesman in Johannesburg or a customer in Jukkasjärvi.

What brands are archetypes?

All brands that affect us on a deeper level contain a story created around an emotionally charged character or personality. Without it, we would simply not be able to have an emotional relationship with the brand. In the transparent and global world we live in, where the rational characteristics of competing products are simple to compare, the story around the brand increasingly becomes the only relevant factor for the buyer to distinguish it by.

So we buy sneakers from Nike not because its shoes are the best but because we want to share the feeling of winning and crushing all resistance. And we buy a motorcycle from Harley-Davidson not because its bikes are better than everyone else but because it makes us feel like a rebel – a Hell’s Angel – whether we live in the suburbs of London or in the deserts of Nevada.

Nike thus represents the archetypal champion/hero, and Harley-Davidson the archetypal rebel/outlaw.

Other trademarks that may be linked to the archetypes is Disney the jester, 3M the creator, Jeep the adventurer, IBM the ruler, Haagen Dazs the lover, McKinsey the thinker, IKEA the universal man and Virgin the rebel.

A rebel, a jester and a common man

That Virgin is such an obvious rebel, the company can thank its, founder Richard Branson for. It is his nature, business philosophy and values reflected in the brand’s personality. Unfairly simple, one might think. But the same principle applies in fact for most strong brand archetypes.

A company’s values and purpose are a consequence of the founder’s or management’s values and vision – even if they are all too rarely identified and formulated. And values, purpose and vision in turn create the conditions for the archetype the brand will (credibly) be associated with.

Disney’s jester archetype is recognized in the company’s purpose: “Make people happy.” And what is the heart of everything that IKEA – the common man (everyman) – does? Well, to “offer a complete range of homewares at prices so low that as many as possible will be able to afford them”. (Ikea’s vision is, moreover, “Creating a better everyday life for many people.”)

What is your brand archetype?

Unlike IKEA, Virgin and Disney, most companies do not have a story and narrative that offers a natural archetype. To identify the genuine and true archetype for your brand needs a systematic structure.

One of the most useful archetype models is Carol S. Pearson’s system consisting of 12 prime archetypes. Carol S. Pearson is a professor of leadership studies at the University of Maryland at College Park, and is author of books like “Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World” and “The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes”.

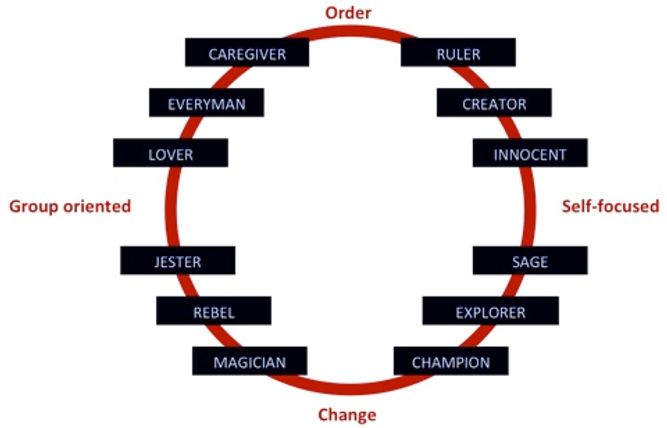

Her system, which is based on Jung’s work, consists of two dimensions: self-focused vs. group-oriented and order vs. change. For example, if the culture of your company is to strive, or to offer, good order – to have control – you are likely an archetype in the upper semicircle. If you also tend to focus more on what is possible to make than what the customers think they need or want, your correct archetype will be on the right side. The truth is thus the archetypal ruler, creator or innocence.

The names of the archetypes can vary. Warriors may also be called champions and heroes; the rebel might be called outlaw or anti-hero; the joker a jester or rogue; adventurers could be called explorers or pathfinders; sages can be called wise ones or gurus; innocents can be called naïf’s or saints; the creators can be called innovators and artists, and so on. But the meaning of each archetype is always the same.

The most notable magician

The magician is for example an archetype who makes things happen, who brings visions to life. Magicians can be framed in many different forms, from the obvious Gandalf in Lord of the Rings to Vianne in Lasse Hallström’s film Chocolat. But regardless of the guise, we are fascinated by the magician’s ability to make the impossible possible. A Magician’s motto is “I make things happen”, his goal is to realize dreams, and his strategy to articulate an exciting vision. And then follow it.

A magician brand is characterized therefore by its power to open new horizons or opportunities for customers. Its product or service may be in constant change, but it is user friendly and it drives development forward. Apple (as well as the company’s founder Steve Jobs) is probably one of the most notable magicians.

Make your mark to a legend

Pearson’s system is therefore an excellent tool for identifying the real and true archetype for your brand. But before you tackle it, ask these five questions of yourself:

- How well known is our story today?

- How consistent is it?

- Do people understand its meaning? Does it convey the same meaning for everyone?

- How credible and motivating is it?

- Which famous character, or archetype, fits into our story?

If you manage to connect your brand to an archetype, and thus to a strong and rich story, you have laid the groundwork for something powerful – you have given birth to a legend.

Or, as Scott Bedbury, former marketing director at both Nike and Starbucks, said:

“A brand is a metaphorical story that … connects with something very deep – a fundamental human appreciation of mythology…”

Companies that manifest this sensibility invoke something very powerful.

Sources: Books mentioned above, by Carol S. Pearson and Margret Mark, article by Jon Howard-Spink, What is your story? And who is your brand?. Originaly posted in Swedish on The Brand-Man, here and here.